In a country where a third of the population still lives below the poverty line, resourceful female artisans have joined forces to purposefully craft their own destiny. W4 celebrates the work of Paulina Samata and the Mbeya Bamboo Women’s Group, working in the vanguard of Tanzania’s equitable and sustainable development.

In a country where a third of the population still lives below the poverty line, resourceful female artisans have joined forces to purposefully craft their own destiny. W4 celebrates the work of Paulina Samata and the Mbeya Bamboo Women’s Group, working in the vanguard of Tanzania’s equitable and sustainable development.

Located on the main trade corridor into central Africa, Tanzania’s regional capital of Mbeya shows promising signs of growth, with a cluster of small shops, hotels, petrol stations and a housing development springing up along the busy main road. Stray from the thoroughfare, however, and you find yourself in cramped neighborhoods whose bustling dirt roads are home to throngs of street vendors: men and women jostling for a bit of dirt pavement to sell their wares.

This is a common sight in a region where 80% of the population is concentrated in rural villages and ekes out a precarious existence based on subsistence farming. While the birth rate in these communities remains critically high, growth rates in agriculture are negligible and insufficient to lift an expanding rural population out of poverty. Education is the key to escaping this cycle of poverty, but for rural girls and women, education is firmly out of reach. Despite the Tanzanian government’s efforts to improve boys’ and girls’ access to primary and secondary schooling, time-consuming domestic responsibilities, as well as early pregnancy and marriage, force many girls to abandon their schooling.

Paulina Samata, a single mother of four and the driving force behind a flourishing women’s cooperative in Mbeya, understands only too well the daily challenges faced by rural girls and women. Born and raised in Mhaji village, a small and very poor community in the Iringa region, Paulina ran around barefoot as a young girl, helping her mother to raise the family after the premature death of her father. Today, Paulina is the leader of the Mbeya Bamboo Women’s Group and she invests her energy and talent in other young women, giving them the opportunity to become entrepreneurs. “Having been so poor myself, one can understand only too well what poverty is and the burden of the poor”, she tells W4, “especially the burden poor women carry.”

Paulina Samata, a single mother of four and the driving force behind a flourishing women’s cooperative in Mbeya, understands only too well the daily challenges faced by rural girls and women. Born and raised in Mhaji village, a small and very poor community in the Iringa region, Paulina ran around barefoot as a young girl, helping her mother to raise the family after the premature death of her father. Today, Paulina is the leader of the Mbeya Bamboo Women’s Group and she invests her energy and talent in other young women, giving them the opportunity to become entrepreneurs. “Having been so poor myself, one can understand only too well what poverty is and the burden of the poor”, she tells W4, “especially the burden poor women carry.”

A social entrepreneur is born

Paulina’s opportunity came in 1985, when the Small Industries Development Organization (SIDO) offered a two-year bamboo-weaving training program to local unemployed women, with the aim of enabling the women to obtain employment either at the SIDO Bamboo College or through the establishment of their own businesses. After graduation, Paulina moved to Mbeya and accepted a job working for an Indian businessman. For the next ten years, she and her 24 colleagues worked for a monthly salary of TSH 1400 (the equivalent of 1.20 USD at the time) making bricks for construction and producing bamboo handicraft items. Occasional overtime allowed some of the employees to supplement their income with a mere 2.5 cents per item crafted. Though the women were provided with a room, they were expected to cover their food and living expenses with their meager earnings.

When the owner of Bamboos, Bricks and Handicrafts closed his business and moved to Dar es Salaam, Paulina was stirred into action. Together with her colleagues, Sarah Daudi and Helena Ngilangua, a widow with two children, Paulina formed the Mbeya Bamboo Women’s Group. Created out of necessity, the group has remained true to its original raison d’etre over the past 15 years – helping to provide sustainable work and incomes for the region’s most vulnerable women.

When the owner of Bamboos, Bricks and Handicrafts closed his business and moved to Dar es Salaam, Paulina was stirred into action. Together with her colleagues, Sarah Daudi and Helena Ngilangua, a widow with two children, Paulina formed the Mbeya Bamboo Women’s Group. Created out of necessity, the group has remained true to its original raison d’etre over the past 15 years – helping to provide sustainable work and incomes for the region’s most vulnerable women.

Since founding Mbeya Bamboo Women’s Group’s more than two decades ago, Paulina’s courage, tenacity and determination have been unwavering. In 2004, she witnessed the withering of the group that she launched with no marketing experience and no client base, falling to just two members, owing to dwindling sales. Undaunted, Paulina established a firm and ambitious business plan, prioritizing the pursuit of new markets and customers. Further goals included the creation of a website, improved record keeping, the purchase of a bamboo forest in order to secure raw material supplies, and the construction of a larger workshop on the main road.

“I want to teach them a trade so that they can have a better life”

Today, business is thriving. The women’s large workshop, situated in the village of Uyole, is a hive of activity. Twenty-five industrious women fashion bamboo sticks into a range of beautiful products, from solid chairs and tables to delicate baskets. Some women work with their babies strapped to their backs: a stark reminder that the majority of them are the sole carers and income providers in their families – responsible for paying for shelter, food, medical care and school fees for themselves and their children.

Today, business is thriving. The women’s large workshop, situated in the village of Uyole, is a hive of activity. Twenty-five industrious women fashion bamboo sticks into a range of beautiful products, from solid chairs and tables to delicate baskets. Some women work with their babies strapped to their backs: a stark reminder that the majority of them are the sole carers and income providers in their families – responsible for paying for shelter, food, medical care and school fees for themselves and their children.

A fully-trained bamboo weaver earns an average income of 53 USD a month. Monthly rent for the most basic of rooms ranges from $7 to $14, which leaves $1.33 a day to cover other expenses. Some women, if they have no money left for transport, regularly walk up to five miles to get to work each morning. At the Mbeya Bamboo Women’s Group, all income from sales (after a deduction of 15% for overhead costs) is distributed to the workers. If sales are higher one month, the women receive a higher monthly salary. The cooperative provides a safe, stable and fair environment in which each woman is supported and in which her dignity is restored.

Paulina also offers training courses free of charge. Her sole requirement is that the trainees stay with the community for at least six months. The young women, most of whom have never benefited from any formal education, receive $2.25 a week as an incentive to complete the training course. For Paulina, what is most important is that the women acquire a valuable skill. “I do not like young girls to work as domestic helpers,” says Paulina, “I want to teach them a trade so that they can have a better life.”

In 2005, Paulina caught sight of Flaha Mwinami, a 19-year-old, single mother of two, selling sugar cane on the street and persuaded her to come and train with the group. Flaha had been abandoned by her parents as a toddler and raised by her grandparents. Now aged 26, Flaha is able to send her son and her daughter to school, thanks to the income she earns crafting bamboo. She is also learning a host of other new skills, such as accounting, book-keeping and English. Business trips to Dar es Salaam and Malawi not only give her an insight into the world of marketing but also open her eyes to different cultural perspectives, new ideas and contrasting lifestyles. Above all, Flaha has been saved from the dangers of prostitution, to which countless young Tanzanian women fall prey.

Paulina, who has now trained over 60 women, speaks proudly of her recruits: “The women are very intelligent: they use the income generated from their bamboo sales to buy food, medicine and malaria prophylactics and to undergo HIV/AIDS tests.”

Building a culture of sustainability: “The wonder wood of the poor”

Paulina’s vision conceives of development in rural Tanzania as more than simply economic growth. While providing jobs and revenue for young women, girls and orphans, Paulina and her fellow entrepreneurs recognize that environmental issues are the meta-context within which poverty eradication and other developmental goals are to be sought in Tanzania. Underpinning all that they do is their deep respect for their natural surroundings.

Abundant forests, ranging from lush tropical jungles to desert scrub, carpet the contours of Tanzania. Yet indiscriminate tree felling and unsustainable logging is reducing much of the once-rich forests to bare land. 90% of the population in Tanzania still relies on charcoal and firewood for household cooking fuel. Rapid urban growth in recent years has created a higher demand for charcoal, dramatically increasing pressure on the country’s woodlands. UN figures suggest that large-scale deforestation has reduced the country’s forest cover over the last 40 years from 6.3 hectares per capita in 1961 to just .08 hectares today.

Such radical depletion of forest resources undermines the country’s potential for sustainable development and has a direct impact on women in rural areas who are now forced to walk long distances for fuel wood.

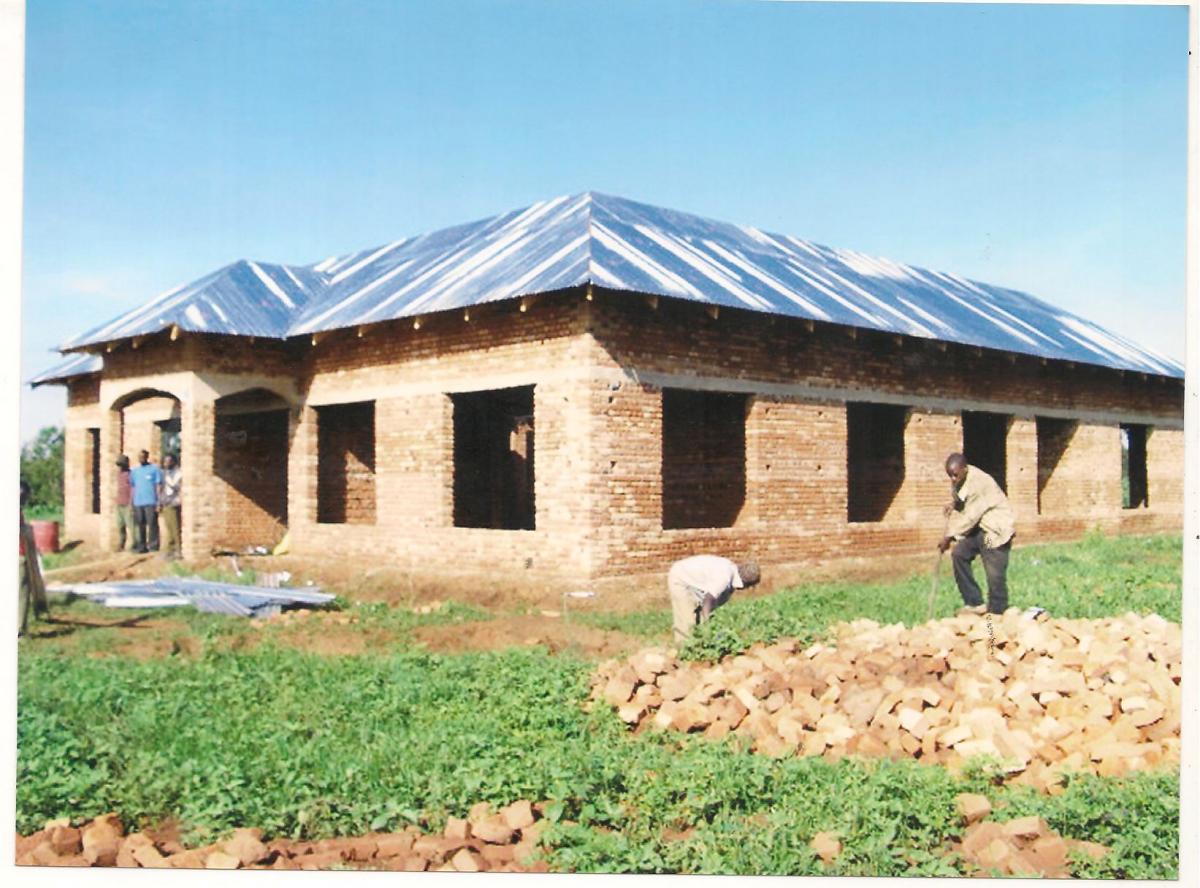

However, a bird’s-eye view of Tanzania reveals a patchwork of denuded forest areas counterbalanced by flourishing, vibrant bamboo plantations covering an estimated 127,000 hectares. Designated the “wonder wood of the poor,” bamboo is deemed to be the fastest-growing plant on the planet and a viable replacement for wood. “When a tree is cut, it is gone,” remarks Paulina, “but when you cut bamboo, it sprouts again in even greater numbers.” She and her colleagues have planted bamboo seedlings in the regions of Mbeya, Iringa and Njombe, and they hope to secure support for more extensive plantings in the future. The cooperative uses 30-34 sticks a month to fashion the women’s products and simultaneously collaborates with local NGOs to provide small rural schools with computers and thus educate villagers about the importance of bamboo, as a source of both income and sustainable energy. Their most ambitious project to date has been the construction of a Community Service Centre and Orphanage in Njombe, which they hope will be completed by October of this year. “I want everyone to understand the potential of bamboo, and the many things you can do with this plant,” says Paulina.

However, a bird’s-eye view of Tanzania reveals a patchwork of denuded forest areas counterbalanced by flourishing, vibrant bamboo plantations covering an estimated 127,000 hectares. Designated the “wonder wood of the poor,” bamboo is deemed to be the fastest-growing plant on the planet and a viable replacement for wood. “When a tree is cut, it is gone,” remarks Paulina, “but when you cut bamboo, it sprouts again in even greater numbers.” She and her colleagues have planted bamboo seedlings in the regions of Mbeya, Iringa and Njombe, and they hope to secure support for more extensive plantings in the future. The cooperative uses 30-34 sticks a month to fashion the women’s products and simultaneously collaborates with local NGOs to provide small rural schools with computers and thus educate villagers about the importance of bamboo, as a source of both income and sustainable energy. Their most ambitious project to date has been the construction of a Community Service Centre and Orphanage in Njombe, which they hope will be completed by October of this year. “I want everyone to understand the potential of bamboo, and the many things you can do with this plant,” says Paulina.

Marketing beyond borders

The women have produced a catalogue of their beautiful creations, which they distribute widely to hotels, gift shops and retailers in Dar es Salaam – their primary market, after direct sales from their workshop in Mbeya. However, the cooperative is expanding its sales beyond the borders of Tanzania and Paulina is exploring potential new markets in Zambia, Malawi, Kenya and Uganda. Current exports are through an intermediary, but Paulina’s goal is eventually to manage the exports so that more of the income generated by sales will go directly to her talented artisans and, in turn, to the local community. The internet could prove to be an invaluable tool in achieving this ambition. Meanwhile, the women continue to develop new product designs and, to meet a growing demand, are in the process of introducing new machinery that will serve to increase productivity without detracting from the originality and artisan quality of their work.

The women have produced a catalogue of their beautiful creations, which they distribute widely to hotels, gift shops and retailers in Dar es Salaam – their primary market, after direct sales from their workshop in Mbeya. However, the cooperative is expanding its sales beyond the borders of Tanzania and Paulina is exploring potential new markets in Zambia, Malawi, Kenya and Uganda. Current exports are through an intermediary, but Paulina’s goal is eventually to manage the exports so that more of the income generated by sales will go directly to her talented artisans and, in turn, to the local community. The internet could prove to be an invaluable tool in achieving this ambition. Meanwhile, the women continue to develop new product designs and, to meet a growing demand, are in the process of introducing new machinery that will serve to increase productivity without detracting from the originality and artisan quality of their work.

The resourcefulness, creativity and perseverance of Paulina and the other women in the Mbeya Bamboo Women’s Group are exemplary. We invite you to learn more about their work and how you can support these women as they work to create sustainable, environmentally-friendly livelihoods for themselves and other women in Tanzania.

© Women’s WorldWide Web 2012

1 Comment

Hi congrats for the good work. Am a bamboo enthusiast from Kenya any leads on where I can get seeds will be appreciated. Thanks