W4 interviews Rachel Lloyd, Founder and CEO of GEMS (Girls Educational & Mentoring Services), a US-based organization aimed at empowering girls and young women, ages 12 to 24, who have been commercially sexually exploited and domestically trafficked in the United States by providing them with access to such vital services as counseling, job and leadership training, healthcare, crisis housing, and court advocacy.

After escaping from commercial sexual exploitation as a teenager herself, Rachel Lloyd founded GEMS (in 1998) as a means of responding to the gap in specialized assistance available at that time for young women at risk of exploitation in the United States. In addition to its acclaimed survivor leadership and empowerment services model, GEMS advocates at local, state and national levels to find solutions to systemic issues that perpetuate the commercial sexual exploitation and domestic trafficking of girls and young women in the United States, while also campaigning to change perceptions of and build support for girls and young women who have been subjected to exploitation.

After escaping from commercial sexual exploitation as a teenager herself, Rachel Lloyd founded GEMS (in 1998) as a means of responding to the gap in specialized assistance available at that time for young women at risk of exploitation in the United States. In addition to its acclaimed survivor leadership and empowerment services model, GEMS advocates at local, state and national levels to find solutions to systemic issues that perpetuate the commercial sexual exploitation and domestic trafficking of girls and young women in the United States, while also campaigning to change perceptions of and build support for girls and young women who have been subjected to exploitation.

W4 – In your book, you describe the general sympathy the public feels for victims of trafficking, but how this attitude quickly changes when you explain that GEMS works with American girls and young women who have experienced commercial sexual exploitation and domestic trafficking. They respond by saying things like: “Teen prostitutes choose to be doing that; aren’t they normally on drugs or something?” What are effective ways of not only responding to, but also changing, this erroneous perception?

We do a lot of public education and training. Yesterday, I was speaking at a conference for 250 law enforcement officials on the theme, “Preconceived Notions about Victims of Trafficking”. Lack of awareness is a widespread problem, but I think that when people receive the necessary education and information, their perception shifts. They’ve just never thought about it before. With most people, it’s not that they hate kids or that they hate American girls, it has just never really occurred to them that what is happening to girls and women here, in America, might be similar to what happens to girls from other countries.

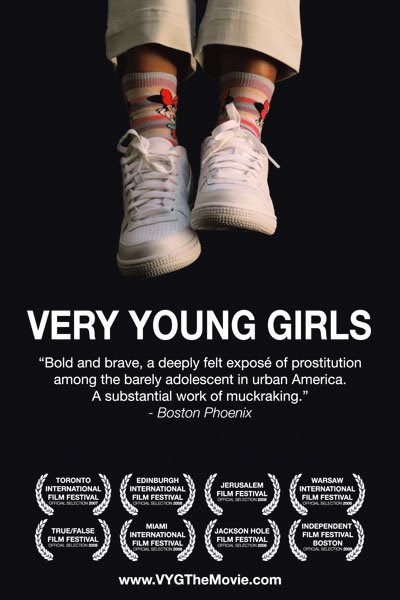

We’ve conducted public education both with the book, Girls Like Us, and the film, “Very Young Girls” (directed by David Schisgall), which has been seen by over 4 million people. The documentary is one of the things I’m most proud of, in terms of the impact it’s had. We continually get emails from people who say “I’d never thought about that before and then I watched the film and I totally connected with these girls.”

What we were very careful to do in the movie—and it’s what I also tried to do in my book— was to make sure that we are presenting survivors and survivors’ voices in a way that isn’t sensationalized, that isn’t marginalizing, that isn’t “Oh, poor little victims”. Rather, we show that we are people, that we are complex people, but no different from you. I think survivors have a critical role to play in humanizing perceptions of other girl and women survivors. I’m not saying the answer is for girls to have to share their experiences all the time, but survivors play a critical role in leading the movement to end trafficking and in really changing how people see girls and women.

W4 – In fact, you depict the girls and young women not as drug-addicted but as love-addicted, terribly vulnerable and profoundly manipulated. Pimps create a pseudo-family structure in which other girls are “wives-in-law”, and these “families” are headed by a man they call “Daddy”. How is GEMS helping to prevent these vulnerable children and youths from becoming commercially sexually exploited/trafficked?

I think the prevention component is really, really complex. We do prevention work in terms of going into schools, high schools, junior high schools, group homes, juvenile detention centers, and talking to girls who are at risk about the realities of the commercial sex industry. But I think real prevention has to go even deeper than that. It has to be about ending child sexual abuse, which makes so many young people so incredibly vulnerable. It has to be about reducing and ending homelessness and the number of young people who are runaways and homeless in our country every year. It has to be about changing economic options for young people. It has to be about ending racism.

The real sort of prevention work is about longterm systemic change, about creating a kind of equity, protecting young people and ensuring that all young people in our country have the same options, opportunities and protection, which just isn’t the case as things stand. That’s why we continually see—over and over again—the same kind of young people being exploited. It’s predominantly low-income girls. It’s predominantly girls of color. It’s girls who have already been through the child welfare system, girls who have already been through the juvenile justice system. It’s girls who have been seen as marginal and have been failed by systems, by adults and by communities.

I feel that GEMS is trying to bring the conversation around trafficking back to these larger, systemic issues because people get very caught up in the “Oh my God, we have to rescue little girls”-thing and they tend to miss how race matters, how class matters, how poverty, gender and equity matter. All of these things matter. If we approach the problem in a myopic way, we are never going to see a real reduction in trafficking.

W4 – The vision of GEMS is to end the commercial sexual exploitation and trafficking of children. You also speak about how you see GEMS more as a girls’ empowerment organization than an anti-trafficking organization. Can you explain this differentiation and why you believe this is an important distinction? Could you tell us a bit about your “Victim, Survivor, Leader” model?

It isn’t about knocking anti-trafficking organizations, but I do think that, in the last couple of years in particular, there has been a way of approaching the issue of trafficking that isn’t always helpful. A kind of rescue-heavy model, using pictures of girls in chains and that kind of thing. It’s not just about rescuing girls, although sometimes we literally have to do that. For example, it’s 3 o’clock in the morning and we have to go get a girl who has been beaten up. That’s part of the work, but that’s not where it ends.

You have to be able to empower that young person to discover her own strength and resilience, which she absolutely has. You have to be able to create systemic change to ensure that that young woman is in a world where she won’t keep getting knocked down at every turn. You have to be able to create economic opportunities and educational opportunities so that she’s empowered to be free of sexual exploitation. That’s the model that we’re about.

I would say that we’re fundamentally a feminist organization. We’re looking at the intersection of race, class and gender. I think that is what our work is really about and the organizations that we tend to be more philosophically aligned with are usually those that are girls’ empowerment-focused. So, I think that’s the distinction. It’s an empowerment, long-term, systemic-change model and an advocacy model. It’s showing that survivors are not just beneficiaries or recipients of services, but survivors are actually running, developing and leading services and creating advocacy and change. Our mission is to end the commercial sexual exploitation of girls and women. We work with young people, girls and women, up to 24 years old, so we don’t just work with children. We’re also concerned about young people who are in the commercial sex industry who may not have been trafficked but didn’t have any other options. Just because you end up in the sex industry and don’t have a pimp, does not mean that you are not being exploited or that you don’t deserve support and services.

The “Victim, Survivor, Leader” model advances along that trajectory. You can’t stay focused on the victim stage forever. If you are treated as a perpetual victim—and sometimes I see that in the movement; it’s believed that if you’ve been trafficked, you’re perpetually damaged—you’ll never be able to do anything. You’ll never really heal. We just put a band-aid on the wounds.

It’s just not true, and it’s so limiting for survivors. Our model is about moving girls and women past that victim stage, really supporting that survivor component, but then moving beyond that. That way, you are not continually defined as just a survivor of something that you experienced, but instead you can define yourself as a leader, whether that’s a leader in your community, in this movement, or a leader in your own life and in your own family. Leadership looks different for different people. I would say that we have lots and lots of leaders at GEMS who lead us in lots of different ways. The leadership stage is, I think, where we are always trying to encourage and empower girls to get to.

W4 – Your book illustrates the profound effect that compassion and belief in the girls’ potential, as shown by some police, judges, prosecutors and FBI agents, can have on the girls you serve. Are these professionals being trained regarding the commercial sexual exploitation of children, and have you seen a shift in the way they provide services?

W4 – Your book illustrates the profound effect that compassion and belief in the girls’ potential, as shown by some police, judges, prosecutors and FBI agents, can have on the girls you serve. Are these professionals being trained regarding the commercial sexual exploitation of children, and have you seen a shift in the way they provide services?

Yes, definitely. I think that training is critical. We spend a lot of time conducting training with law enforcement personnel, with service providers, with social workers. It’s not just law enforcement personnel who need training. Psychologists do, too! It’s often people who you would expect to know better who don’t get this issue. I am a big believer in presenting people with information in a way that feels tangible to them and relates back to concepts that they already understand. For example, we draw parallels with domestic violence and the domestic violence movement, or child sexual abuse. Things that people sort of already understand—and people see that girls and women are victims in those cases. Helping people to see the connections between those issues and the sex industry is really critical.

And we’re seeing massive change. Even yesterday, just being at that conference and speaking, is an example. You couldn’t have even gotten three police officers in a room ten years ago. I mean, really, you couldn’t have! Last year we were able to meet with Commissioner Kelly, the Commissioner of the New York Police Department. We met with a group of advocates with him and I said to him at the end, “I really want you to meet with some survivors. I think it’s very important that you hear from girls and women who have actually had these experiences in New York City and very often did not have positive experiences with law enforcement.” Two weeks later, we came back and we brought a bunch of our young women, and I think New York Asian Women’s Center and Sanctuary for Families had a couple of their folks there too, and for three hours the Commissioner sat and listened to the girls’ stories. We’ve definitely seen a shift.

We’ve seen law enforcement arresting johns, putting more resources into trafficking units and the prosecution process. I definitely believe there is a shift. I don’t think it happens in an hour. For our training for law enforcement, for example, we do a series of national trainings that are three days long and very intensive. I’ve seen cops come in and have the worst attitude towards this issue on the first day—making all kinds of jokes and terrible comments. Then, by day three, they are pounding their fist on the table saying, “We have to stop this right now!”

In fact, one of my staff members was on a panel with a cop just a couple of weeks ago and she came back enthusing about how the cop had been really passionate on the subject. I told her it was the same cop who had participated in one of my training courses a year ago and who was such a jerk in the beginning, I mean REALLY offensive. I had to call him out at the start of the training. I told him, “Look, I will let it go at hour one, but if you are still talking like this on day three, then you and I are going to have a problem.” A year later, he is advocating on panels about the issue! I won’t even repeat what he said in the beginning; they were really offensive comments. So, I felt proud, like a parent, as if I’d seen this cop graduate or something.

Unfortunately, people don’t always get it and then there are the misleading messages that we’ve gotten from the media and our culture, and all the jokes. Look at the recent Secret Service scandal, the jokes about hookers and hoes and prostitutes. It’s so saturated in our culture, the idea that women and girls in the sex industry are inferior, that they are less than and totally different from normal people. I think shifting that perspective is the most important thing that we can do.

W4 – You’ve done a phenomenal job. Actually, it was just about 10 years ago when I first heard about your work through Mishi Faruqee at the Correctional Association. She was always praising your work during the time that I was part of the Juvenile Justice Coalition, from about 2003-2005. It’s amazing how much you’ve accomplished in the past decade. I really do think that perspectives have changed. At least here in New York City, there’s a conversation now that I don’t think existed back then. It’s inspirational.

Thank you! There are definitely those moments where you are, like, Wow! This would not have happened a few years ago. Even the way people are talking about this issue today: in a recent case, the Manhattan District Attorney’s office indicted not only traffickers, but also the delivery car drivers and the cab drivers who were ferrying girls around and who were actually complicit. And the JOHNS! That’s HUGE! I can remember a prosecutor telling me a few years ago that johns aren’t the problem. I remember thinking, “WHAT? Are you serious? Of course, they are the problem. They are doing the buying!” Seeing the District Attorney’s office actually prosecute johns convinces me that there’s been real change.

When you’re doing the work on a daily basis and you go out and see a girl who is thirteen–that’s tough. At times like that it can feel like you’re not able to really make a difference. But I think I am reasonably optimistic about where we are headed.

W4 – What are the different ways in which you measure success at GEMS and how do you evaluate anti-trafficking strategies?

We are evaluating success in pretty standard ways: educational achievements, employment, stable housing, exiting the commercial sex industry, etc. So, there are the quantitative measures, but I think it’s also critical to recognize that it tends to be a long journey for folks. The idea that somebody might come to GEMS and then, two weeks later, leave the old life and she’ll be fine–that’s just not how it happens. Rather, she comes a first time and starts to engage a little bit, but then she disappears. Then she’ll come back and she engages a little bit more, and then she’ll go back to her pimp because he just got released from jail. But then she’ll come back to us again. Over time, we begin to see that she’s still engaged in the search for a new life, the fact that she still comes, even if it’s not consistently. But that door has to continually remain open for her.

I think that measuring success in baby steps, too, is critical. Even simply recognizing the fact that people show up, despite all the stuff they are going through. Seeing girls who come to the program and at first won’t speak or will be really reticent and withdrawn, but then gradually start having things to say and start talking up in group and sharing with their peers—those kind of changes are important, too. Seeing someone’s growing confidence, her growing sense of self. So, I think quantitative success is important, but it’s also critical with any group of people that you are working with to be able to recognize the subtle progress they are making. Nobody’s life is linear and no one is a statistic. People’s lives are complex and you need to be able to appreciate the qualitative kind of successes as well.

W4 – You emphasize that raising awareness, conversation, dialogue and changing perceptions are extremely important in the effort to end the commercial sexual exploitation of children. What are some ways in which individuals can get involved in bringing light to this issue and what other ways can we, on an everyday level, contribute to your work?

W4 – You emphasize that raising awareness, conversation, dialogue and changing perceptions are extremely important in the effort to end the commercial sexual exploitation of children. What are some ways in which individuals can get involved in bringing light to this issue and what other ways can we, on an everyday level, contribute to your work?

It’s one of those issues which can feel overwhelming because people think “this is such a huge issue that I can’t possibly do anything about it”. What we know from other social justice movements is that it’s not just the efforts of charismatic leaders that bring about change, but the everyday efforts of individuals in our communities, in our colleges, in our places of worship, within our families. That’s where real change begins. There are multiple examples of social justice issues that, at one point in history, looked insurmountable and were the status quo but that we have since overcome. Thinking about how we can apply the lessons we’ve learned from other movements is critical.

Often people have hopes that they can sort of turn up and rescue a trafficking victim, but that’s not how it works, nor, necessarily, how people can make the greatest impact. Figuring out your role, where you fit into the circle of influence you have, is important, and your greatest impact could be, for example, hosting a book club to share “Girls Like Us” with other people. What has been amazing about the book is how many women, in particular—and men, too, but it applies mainly to women—have connected with themes in the book, not necessarily because they have been commercially sexually exploited, but because there are some very common themes that have resonance for many women, about being vulnerable as a teenage girl, about abuse, about family problems. It has led women to say, “Oh, I always thought that I would never be able to do that. That’s disgusting. Yet now I’m realizing that this girl was no different from me. I was fortunate that I wasn’t so vulnerable, never met a pimp when I was fourteen years old, but if I had done, perhaps my life would have looked totally different.” I think it’s important to be able to open people’s minds to that.

Another way to drive change is by talking with the men in our lives about this issue and building male allies who will stand up against the demand side of things. We need to resocialize boys and young men, to educate boys and men about masculinity and about how women and girls are treated in our culture: that purchasing another human being is not okay. We lack that discussion with boys and young men. There are lots of good men out there, who were enlightened by girls and young women, but who remain silent. We need to mobilize their support and get them actively involved.

Giving money is always really helpful, but so is creating change in your own circle, in your own community, in the sphere of influence that you have, and thinking carefully about how you can create change. Just changing the conversation is already a powerful step. When someone makes a joke about pimping, you can educate that person. There are guys on our block who have seen our movie and who have come to us and said “I’ve been a gang member” or “I’ve been a drug dealer for…[however long] … and I thought that pimping was just kind of funny. I never understood. I grew up in the streets and never understood the impact that pimping has and what these guys are doing, and now I want to go beat them all up.”

We need to make people feel outraged about this issue and then we need to turn that outrage into practical solutions. So, it’s not just about how I can go rescue a trafficking victim, but about what I’m doing in my life, every day, to end racism, to end poverty, to end gender inequity and recognizing that all those things are linked to trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation and that if we all work together to address those different factors, ultimately, we will see the end of trafficking.

If we don’t, then we’ll see some progress for the next two years while we’ve got all this momentum and all this excitement around the issue but then the world will move on to another issue. No issue stays in the spotlight forever. We have to think about sustainable solutions and where we want to be ten years from now, when the world has moved on and MSNBC has moved on. Where are we at? What dents have we made in the lives of girls and young women?

For all the press coverage we’ve seen in the past couple of years, despite Craigslist shutting down and all the things that we have touted as victories in the trafficking movement, we still haven’t seen a decrease in the number of girls who are approaching us at GEMS. In fact, we’ve seen an increase. This is because, although people are becoming more educated on the issue, we haven’t yet seen a real dent in the number of girls and young women who remain vulnerable and who end up being recruited.

W4 – You wrote in your book: “I felt like the little Dutch boy with his finger in a dam. No matter how hard I tried, it didn’t prevent a whole new generation of children from being bought and sold.” The commercial sexual exploitation and domestic trafficking of children is a massive and grave problem, which can seem insurmountable at times. How do you keep from being overwhelmed and what provides you with hope and the energy to continue your work?

I was talking to a friend in the field about this the other night. She is an Executive Director too. Look, this is tough, tough work sometimes. I was saying actually that I sometimes think it’s tougher just running the organization! Dealing with the budget, management, the fundraising, and staff. It’s the administrative stuff. It’s those aspects and the politics that can actually weigh you down. All these things can overwhelm you. The pressure of funding—there’s never a let-up on that.

What keeps me sane and grounded are my weekly meetings: I still run a weekly group. When I am running my weekly group on a Wednesday night with a group of girls and feeling like, whatever we’re doing, we’re creating a space where girls feel safe and loved and supported, that sustains me. Sometimes, that just has to be enough. If I didn’t have that activity, if I were constantly doing advocacy work or focusing on the systemic change aspects or whatever, I think I’d begin to feel incredibly overwhelmed. But it’s the same if you’re only involved in direct services and not in the activities that address systemic change. I think you have to have a balance of both, but there are times when I think that if everything else stopped tomorrow, if we weren’t doing anything at the national level or political level or any of that—as long as I was still running the program in Harlem, I would be fine because that’s where I feel happiest. That’s where I see the difference.

I come into GEMS every day and I see the girls, who have graduated from our program and who are now on our staff, sitting at the front desk or doing outreach work or working in our admin department or facilitating groups. Just seeing that and knowing it’s possible and seeing it play out over and over again, that drives me. I think the narrative and the movement tend to be very focused on “Oh, this is so hard and difficult!” But there’s very little narrative around survivor strength. About how funny and smart the women are. I love working with teenagers. Young women are a lot of fun to work with too. We cut up all the time at GEMS. I would not want to be anywhere else in the world.

W4 – Would you please share one or two of GEMS’ success stories and explain what factors contributed to these successes?

That is like choosing my favorite child, right? I mean, it’s just the same!

We are seeing success on a continual basis. Two or three weeks ago, I got to watch one of my girls graduate with her Bachelors in Psychology. That was pretty awesome. I don’t want to take away from any of our young women’s individual strengths. SHE’S the one who went to college. SHE’S the one who figured things out. SHE’S the one who did the homework. I feel we are fortunate to be by the side of these girls, supporting and encouraging them and telling them, “No, don’t drop out. It’s okay. You’re going to be alright. You’re going to get through this.” Ultimately, it’s THESE GIRLS doing the work. It’s THESE GIRLS staying away from their pimps. It’s THESE GIRLS making decisions every single day to get up and come to GEMS even if nothing else good is going on in their lives. Even when everything else in their lives is crazy, THEY are still walking through that door and making a choice to be part of a community and to move forward.

I think the girls need a place to be able to do that. I think it’s very hard as a survivor who’s been through all manner of hard experiences and who is facing stigma and discrimination. It’s tough for anyone to make it on her own. That’s why we created a community of young women to encourage and support each other. The young woman who just graduated with her Bachelors is now mentoring. She’s actually the intake coordinator for our mentoring program. She’s mentoring other young women, and I see how other girls look at her thinking “Oh, I want to be like her!”

I remember when she first walked in the door; she was crying her eyes out. She came to us when she saw the film. She had never heard of GEMS before that. She had never talked about her experiences. She walked in and cried for the first three hours. She came back the next day and again the next day after that. She’s on our full-time staff now. She’s got her Bachelors degree. Life has changed very, very dramatically for her. I mean, of course, not everybody has their Bachelors yet, but I could give you a whole array of stories of young women survivors who are doing really, really well in their lives.

Interview conducted by Jenny Yun for Women’s WorldWide Web

© Women’s WorldWide Web 2012