W4 welcomes guest contributor, Tithe Farhana! Farhana is from Bangladesh where she is working as Communications Coordinator for Plan Bangladesh and Co-Manager of the women’s rights advocacy group, Bangladeshi Women’s Voice, while also pursuing her Master’s degree in Development Studies and Environmental Management. Farhana has contributed to Global South Development Magazine, The New Agriculturist, IRIN, and Thomson Reuters.

W4 welcomes guest contributor, Tithe Farhana! Farhana is from Bangladesh where she is working as Communications Coordinator for Plan Bangladesh and Co-Manager of the women’s rights advocacy group, Bangladeshi Women’s Voice, while also pursuing her Master’s degree in Development Studies and Environmental Management. Farhana has contributed to Global South Development Magazine, The New Agriculturist, IRIN, and Thomson Reuters.

18-year old Ruma lives with her 29-year-old husband Kamal in a tin shed in Mirpur slum, Dhaka. They married when Ruma was 14 years old and have a daughter who is two-and-a-half years old.

“When I was in love, I thought family life would be enjoyable. Now, I think getting married so young is terrible”, says Ruma, who once attended school regularly. Kamal works as a pick-up van driver at the nearby Mirpur bus station. “What do I do now that I’m married?” Ruma exclaims. “I take care of my daughter, wash dishes, clean the floor, wash clothes and cook.”

Ruma’s mother Rokeya Banu, now a 35-year-old widow, was also married at the age of 14. Rokeya says she gave consent for her daughter’s marriage at the young age of fourteen because it had become difficult for her to bear the expense of caring for Ruma. In addition, she says, “I feared I would have to pay a huge dowry if she got married at a later age.”

Ruma faced severe medical complications during the birth of her child, and promised herself that she would not “make the mistake of getting pregnant” twice. “I realize how painful it is to become a mother at such a young age. I won’t marry off my daughter before 18,” she asserts.

The Bangladeshi government claims that the national rate of child marriage is declining, but there are no official statistics to demonstrate this. Officially, the legal age for marriage is 21 for boys and 18 for girls, as established over eight decades ago by the National Child Marriage Restraint Act (introduced in 1929 and revised in 1984). However, the Act dictates a relatively minor punishment for those who facilitate child marriages – either one month of prison time or a maximum fine of one thousand taka (approximately 12 USD).

Tragically, despite Bangladesh’s domestic legislation and the international conventions to which it is signatory,[1] countless girls across this country are married before the age of 18. Indeed, one-third of Bangladeshi women today aged between 20 and 24 were married before the age of 15 (according to UNICEF’s 2011 State of the World’s Children report). This state of affairs is essentially owing to insufficient action on the part of the government, in addition to a general lack of public awareness of the harms of child marriage.

Despite widespread public campaigning in recent decades, child marriage remains pervasive, damaging to individual girls, to their children and to society as a whole. On average, girls who marry as adolescents attain lower levels of education, have lower social status in their husbands’ families and in society, report less reproductive control over their own bodies and suffer higher rates of maternal mortality and domestic violence than girls who marry later.

Despite widespread public campaigning in recent decades, child marriage remains pervasive, damaging to individual girls, to their children and to society as a whole. On average, girls who marry as adolescents attain lower levels of education, have lower social status in their husbands’ families and in society, report less reproductive control over their own bodies and suffer higher rates of maternal mortality and domestic violence than girls who marry later.

Unsurprisingly, poverty lies at the heart of this issue. Girls are commonly regarded as an economic and social burden by their families and this, combined with the practice of dowry – the size of which increases as a girl grows older – encourages parents of poor families to marry their daughters off at the earliest age possible. Indeed, because of the pressure of dowry payments, poor families tend to welcome the birth of a male child, while considering the birth of a girl baby a curse.

Perniciously, parents also regard marrying daughters off at an early age as a means of ensuring their daughters’ and their families’ “honor”. Severe social stigma attaches to extramarital relations and girls and young women invariably bear the brunt of even the slightest suspicion of any damage to a female’s “honor”, even in cases of harassment or rape. Households tend to be run autocratically by the father, who often arranges the marriage of his teenage daughter(s) without consulting his daughter(s) or even his wife. In this context, teenagers (particularly girls) have little opportunity to express dissent in the face of decisions taken by their parents.

Bangladesh is only one of many countries blighted by child marriage. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) predicts that by 2020 there will be 50 million wives under the age of 15 across the world. This is a catastrophic projection, particularly for child brides like Ruma, girls who lack the skills, knowledge and livelihood opportunities offered by schooling and are confined to lives within their homes.

Bangladesh is only one of many countries blighted by child marriage. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) predicts that by 2020 there will be 50 million wives under the age of 15 across the world. This is a catastrophic projection, particularly for child brides like Ruma, girls who lack the skills, knowledge and livelihood opportunities offered by schooling and are confined to lives within their homes.

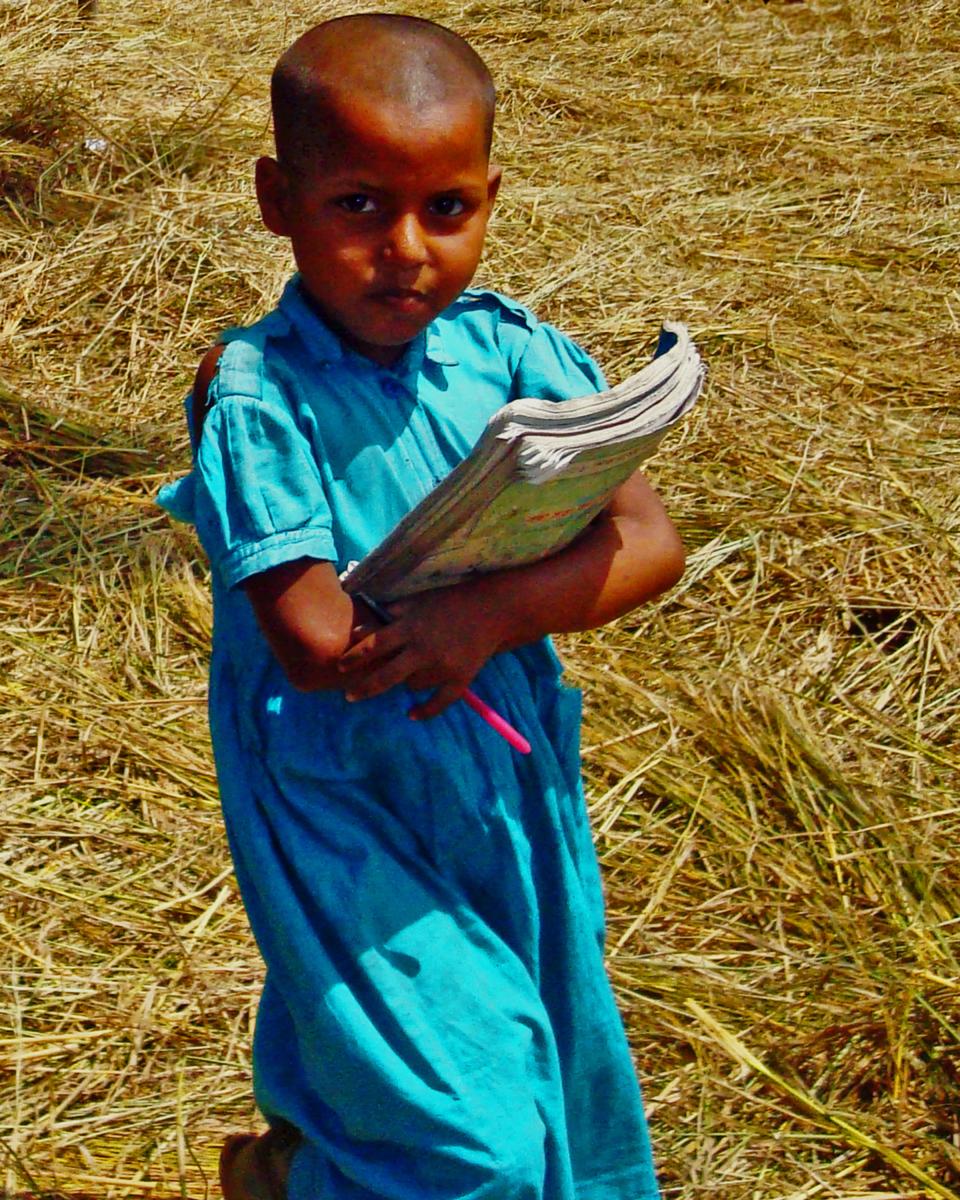

Against this bleak background we can, however, set the good news of what has come to be known as “the girl effect”: a growing awareness of the imperative to protect girls’ rights and the many crucial benefits of doing so. When a girl is able to go to school and complete her education, she gains skills and qualifications that enable her to earn a reliable income and sustain herself and her family, meanwhile contributing to the wellbeing of her entire community. Girls also escape the health risks associated with early motherhood when they are educated because they become more confident, informed and empowered to choose when they wish to start their own families. There is extensive evidence that educated women are more likely to start their families later, have healthier children and send their children to school. In the struggle to break the intergenerational cycle of poverty, education is key: it equips girls and young women with the necessary skills and qualifications to determine their own futures.

Today, as we celebrate the first internationally-recognized Day of the Girl Child, let us renew our resolve to eradicate the practice of child marriage and the harms it entails. Concrete action is called for. We must step up efforts to educate families about the damaging and even dangerous consequences of child marriage, as well as the great and sustained benefits of girls’ education, not only for individual girls but also for their families and communities at large. All the while, we must bring pressure to bear on governments to strengthen the relevant laws and ensure their practical enforcement.

Take action here. Make your voice count to put an end to child marriage, to guarantee every girl’s right to a childhood and education, her right to a healthy development and her right to determine her own future, with the Girls Not Brides campaign.

[1] In 1984 Bangladesh acceded to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which prohibits child marriage (and stipulated 18 as the minimum age in its General Recommendation in 1979). Bangladesh also ratified the UN Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage and Registration of Marriages in 1998. This Convention requires signatory states to obtain consent from both parties entering into a marriage and to establish a legal minimum age for marriage.

© Women’s WorldWide Web 2012