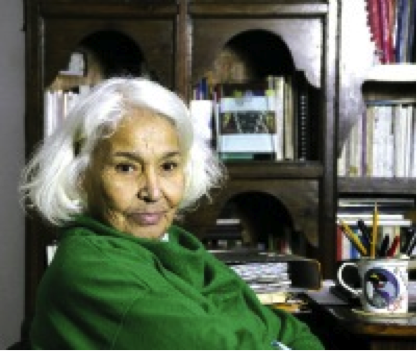

Women’s Worldwide Web salutes the Egyptian novelist, activist, and physician Dr. Nawal el Saadawi for her life-long advocacy of women’s and children’s rights, particularly her courageous and passionate efforts to eradicate the practice of female genital mutilation.

Women’s Worldwide Web salutes the Egyptian novelist, activist, and physician Dr. Nawal el Saadawi for her life-long advocacy of women’s and children’s rights, particularly her courageous and passionate efforts to eradicate the practice of female genital mutilation.

We would also like to pay tribute to Waris Dirie, who created the Desert Flower Foundation to combat female genital mutilation and to promote sustainable economic projects in Africa. Dirie’s spellbinding memoir, Desert Flower: The Extraordinary Journey of a Desert Nomad, depicts her barefoot, nomadic childhood in the deserts of Somalia— where she helped her family to herd sheep and goats, before running away, alone, at the age of thirteen, to escape an arranged marriage to a man in his sixties—and her deeply hazardous odyssey to London, where, after working as a house servant, she became an internationally renowned supermodel, then a mother and, finally, a powerful advocate against female genital mutilation.

Desert Flower (co-written with Cathleen Miller) is a great adventure story, by turns harrowing, touching, and funny. Refreshingly devoid of self-pity, the memoir turns a clear eye on Dirie’s suffering, never sensationalizing, even when it comes to the heartbreaking description of her own experience of ritual cutting as a very little girl, and her bewilderment in the face of the disappearance of other girls, who died from complications following the procedure. “As we traveled throughout Somalia, we met families and I played with their daughters,” she remembers, recounting her childhood days. “When we visited them again, the girls were missing. No one spoke the truth about their absence or even spoke of them at all.”

Mercifully, Dirie survived the severe infection that wracked her body after her own infibulation, but endured agonizing pain with every menstruation, which, she tells us, lasted for ten days each month—until a surgery in London allowed her to menstruate and urinate more freely. Her delight and relief at being able to urinate quickly and without pain are tremendous, and deeply moving: “I could sit down on the toilet and pee—whoosh! There’s no way to explain what a new freedom that was,” she exclaims.

With great pride, Dirie accepted the United Nations’ invitation to become a Special Ambassador and join the international campaign to eradicate female genital mutilation. Towards the end of her memoir, she delineates the dangers and consequences of the ritual, bringing home the urgency of her advocacy work:

“The operations are usually performed in primitive circumstances by a midwife or village woman. They use no anesthetic. They’ll cut the girl using whatever instruments they can lay their hands on: razor blades, knives, scissors, broken glass, sharp stones—and in some regions—their teeth.The process ranges in severity by geographic location and cultural practice. The most minimal damage is cutting away the hood of the clitoris, which will prohibit the girl from enjoying sex for the rest of her life. At the other end of the spectrum is infibulation, which is performed on 80 percent of the women in Somalia. This was the version I was subjected to. The aftermath of infibulation includes the immediate complications of shock, infection, damage to the urethra or anus, scar formation, tetanus, bladder infections, septicemia, HIV, and hepatitis B. Long-term complications include chronic and recurrent urinary and pelvic infections that can lead to sterility, cysts and abscesses around the vulva, painful neuromas, increasingly difficult urination, dysmenorrhea, the pooling of menstrual blood in the abdomen, frigidity, depression, and death.”

Desert Flower ends with Dirie’s loving reflection on her parents’ role in her own childhood suffering and adult losses—and an urgent, uplifting appeal for the future:

“In spite of my anger over what has been done to me, I don’t blame my parents. I love my mother and father. My mother had no say-so in my circumcision, because as a woman she is powerless to make decisions. She was simply doing to me what had been done to her, and what had been done to her mother, and her mother’s mother. And my father was completely ignorant of the suffering he was inflicting on me; he knew that in our Somalian society, if he wanted his daughter to marry, she must be circumcised or no man would have her. My parents were both victims of their own upbringing, cultural practices that have continued unchanged for thousands of years. But just as we know today that we can avoid disease and death by vaccinations, we know that women are not animals in heat, and their loyalty has to be earned with trust and affection rather than barbaric rituals. The time has come to leave the old ways of suffering behind.”

For a dramatic short film on the subject, see Tahara, by Sara Rashad. Tahara is the story of Amina, an Egyptian housewife living in Los Angeles, who must decide whether she will follow tradition and circumcise her daughter, Suha, or abandon this age-old practice and save Suha from circumcision. Despite its illegality, Amina feels strongly that she must continue this tradition because of pressure she receives from her mother, Zeinab, when her husband is away on a business trip.

And, for an award-winning new documentary on FGM, look out for Mrs Goundo’s Daughter (by Barbara Attie and Janet Goldwater), which recounts a Malian mother’s fight for asylum in the U.S. to protect her two-year-old daughter from female genital mutilation. The film will have its national broadcasting premiere in the U.S. on February 9, 2011. For more details click here.

Finally, for a book examining the social dynamics of female genital mutilation, see: Changing a Harmful Social Convention: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting, published by the United Nations Children’s Fund.This book explores the extent to which FGM/C is an important part of girls’ and women’s cultural gender identity in those communities where it is practiced. The procedure imparts a sense of pride, of coming of age, and a feeling of community membership. Moreover, not conforming to the practice stigmatizes and isolates girls and their families, resulting in the loss of their social status. The social expectations surrounding FGM/C represent a major obstacle to families who might otherwise wish to abandon the practice. Changing a Harmful Convention is a contribution to the growing movement to end the practice around the world.

Finally, for a book examining the social dynamics of female genital mutilation, see: Changing a Harmful Social Convention: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting, published by the United Nations Children’s Fund.This book explores the extent to which FGM/C is an important part of girls’ and women’s cultural gender identity in those communities where it is practiced. The procedure imparts a sense of pride, of coming of age, and a feeling of community membership. Moreover, not conforming to the practice stigmatizes and isolates girls and their families, resulting in the loss of their social status. The social expectations surrounding FGM/C represent a major obstacle to families who might otherwise wish to abandon the practice. Changing a Harmful Convention is a contribution to the growing movement to end the practice around the world.

Key Facts about Female Genital Mutilation from the World Health Organization

- Female genital mutilation (FGM) includes procedures that intentionally alter or injure female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

- The procedure has no health benefits for girls and women.

- Procedures can cause severe bleeding and problems urinating, and, later, potential childbirth complications and newborn deaths.

- An estimated 100 to 140 million girls and women worldwide are currently living with the consequences of FGM.

- It is mostly carried out on young girls some time between infancy and the age of 15.

- In Africa, an estimated 92 million girls aged 10 years and above have undergone FGM.

- FGM is internationally recognized as a violation of the human rights of girls and women.

If you would like to learn more about FGM and discover how you might help in the global campaign to eradicate the practice, please visit:

The Desert Flower Foundation by Waris Dirie

© Women’s Worldwide Web 2011