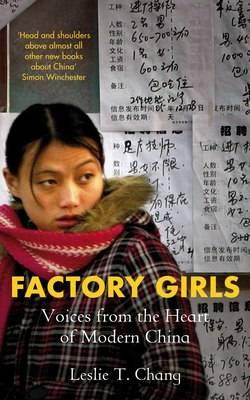

“Often lost in the telling are the invisible foot soldiers who made China’s stirring rise possible: the country’s 130 million migrant workers, the subject of Leslie T. Chang’s Factory Girls.” – New York Times

Leslie T. Chang lived in China for a decade as a correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, specializing in stories that explored how socioeconomic change is transforming institutions and individuals. She has also written for National Geographic. Factory Girls is her first book.

Leslie T. Chang lived in China for a decade as a correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, specializing in stories that explored how socioeconomic change is transforming institutions and individuals. She has also written for National Geographic. Factory Girls is her first book.

A graduate of Harvard University with a degree in American History and Literature, Chang has also worked as a journalist in the Czech Republic, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. She was raised outside New York City by immigrant parents who forced her to attend Saturday-morning Chinese school, for which she is now grateful.

She is married to Peter Hessler, who also writes about China. She lives in Colorado.

Women’s Worldwide Web interviews Leslie Chang, author of the acclaimed book Factory Girls.

In Factory Girls, Leslie Chang tells the story of women in contemporary China who have migrated from their rural villages in search of a better life in the coastal factory cities. Factory Girls focuses on the lives of two young women, Min and Chunming, whom Chang follows over the course of three years as they attempt to rise from the assembly lines of Dongguan, an industrial city in Southeastern China.

Chang portrays a world of ups and downs as the women explore their new-found opportunities and independence, switch jobs, take evening English classes or computer classes, navigate relationships, and, above all, try not to lose touch with each other – for, as Chang writes, “The easiest thing in the world is to lose touch with someone.” The worst difficulties that the migrant women face are not so much the living conditions and low pay, but “the loneliness and the pressure to keep moving on, moving up, and improving their lives; feeling like there would be no one taking care of them if they failed; that they could only go back to the countryside in shame if they didn’t succeed in the city.” Factory Girls depicts both the complex migrant experiences of many women in contemporary China and the wider story of countless impoverished women throughout the world who struggle on a daily basis to surmount hardship and improve their lives.

As a Chinese-American, Chang weaves her own family history into the contemporary stories of the two central figures, Min and Chunming. In this way she gives the current migration of workers a historical parallel – illustrating the historical roots of rural-urban migration in China.

W4: Could you tell us how the idea of your book took shape and describe the circumstances under which you chose to live in South China in the factory town of Dongguan?

LC: I was a reporter with the Wall Street Journal, looking for a subject that could be expanded into a book— something that would be distinctively representative of China. Obviously, there are countless amazing stories in China and there’s no way you can write about everything. But there are certain stories that tell the larger story.

The foreign press, including the Wall Street Journal, had already published stories about the terrible living conditions of the factory workers. The media tended to portray migration as a desperate act, without much payoff. I suspected that the situation was more complex than that—perhaps things were not so black and white. Migration in China has been taking place for decades, as millions of people have chosen to try their luck in cities, rather than remain in rural areas, subsisting as farmers. I wanted to tell individual stories and depict the experience of migration from the workers’ points of view.

W4: As we read about the two central figures, Lu Qingmin and Wu Chunming, and their perseverance in the face of adversity in their new surroundings, we are inspired by their courage, self-reliance, and talent for reinvention. Were you similarly inspired or touched?

LC: Yes, definitely. And that was not something I had expected I thought I would learn a lot about the difficulties of the girls’ lives and maybe get to know them, but I had no idea I would come away from my meetings feeling so personally inspired. I was very touched by their stories and felt connected to them in a way I couldn’t have anticipated. I felt we were engaged in parallel endeavours: I was trying to find my way in journalism and write a book; the women I met were trying to find their way in the factory world, to rise up and make something better of their lives. Our lives were so different, in terms of education and class and national background, yet I felt that our stories were connected in our common aim to realize our potential.

W4: You integrate the story of your own family history with that of the migrants’ experience; at what stage in your writing did you decide to incorporate this story?

LC: It was when I came back from visiting Qingmin in her village, just after the Chinese New Year. I had started my book leave from the Wall Street Journal. I had more free time, so I decided to visit my family village in Jilin to find out who was still living there and whether there was anybody who might have known my grandfather. I thought there must be an interesting way to work these two stories together. For hundreds of years people have been leaving their rural villages in search of a better life, and I wanted to depict this historical parallel rather than keep the story of Dongguan purely in the present—with no past, no history. I felt it would be somehow an incomplete story of China without the historical parallel; there is so much history everywhere, even though people don’t talk about it.

W4: Your book gives an uplifting impression of the contemporary Chinese female migrant experience, insofar as the women do, in spite of the difficulties of their lives, achieve a certain amount of independence, fulfil ambitions, and even achieve social mobility in their new urban environments (which they were unable to achieve in). How representative is this of the female migrant population in China?

LC: I think it’s definitely a mixed picture. I agree with you that there are two sides to the coin: there are opportunities for social mobility for such women, there are also constraints, dangers, and, sadly, cases of abuse. This is a theme in the book. Coming to the city is, in many ways, liberating and empowering for such women, not least because the alternative is a traditional life in rural China, which the women do not want. But what these women find in the city is not, by any stretch of the imagination, an easy life. Their living conditions and the working conditions in the factories are extremely harsh. In the course of reporting, however, I discovered that, although life was very difficult for these women in the city, the difficulties they found most great were not those that you or I might, from the outside, imagine.

LC: I think it’s definitely a mixed picture. I agree with you that there are two sides to the coin: there are opportunities for social mobility for such women, there are also constraints, dangers, and, sadly, cases of abuse. This is a theme in the book. Coming to the city is, in many ways, liberating and empowering for such women, not least because the alternative is a traditional life in rural China, which the women do not want. But what these women find in the city is not, by any stretch of the imagination, an easy life. Their living conditions and the working conditions in the factories are extremely harsh. In the course of reporting, however, I discovered that, although life was very difficult for these women in the city, the difficulties they found most great were not those that you or I might, from the outside, imagine.

I expected that the most difficult aspects would be the gruelling work, the low pay, the grind of the assembly line and the poor food in their dormitories. But, in fact, the women weren’t so concerned about these aspects. They sort of accepted that work was going to be hard, the pay was going to be low; they were accustomed to poor living conditions and poor food. What they really found hard were their feelings of loneliness and the pressure to keep moving on, moving up, improving their lives; the sense that there would be no one to take care of them if they failed. The fear that they could only go back to the countryside in shame if they didn’t succeed in the city. So it was not that their lives were easy, but that the difficulties they emphasized were different from what I had expected. The emotional stress, pressure, and loneliness.

W4: In your book, you describe the night school classes (English lessons, computer classes) in which the women enroll to improve their job prospects, as offering a more successful ‘model of education’ than that offered by the state-run rural schools (where they were unable to complete their education). Do you think the night schools are an important part of the urban migrant landscape and are they useful to the women in terms of continuing their education?

LC: Definitely. I wanted to explore the migrant workers’ lives through the lens of these different ‘markets’. There was the ‘education market,’ for example, consisting of the commercial night schools, and the ‘marriage market,’ where people were trying to match up and find mates. I wanted to depict Dongguan through these small worlds. There was the ‘English language market,’ where people would learn English in bizarre and often not very successful ways. And the ‘direct sales market,’ which offered all sorts of schemes to make quick money. I think all these worlds are fascinating. What ties them together is the incredible hunger for self-improvement felt by the people inhabiting them.

Compared with traditional education, the commercial education market is by no means the answer to China’s problems. It can only be a stopgap measure to help young people learn basic skills. But what was clear to me was that the traditional education system was so removed from the needs of these young people that it was basically irrelevant. The migrant workers I met were very intelligent and resourceful, but almost all of them said to me, “Oh, I did really badly in school. I was a terrible student. I was unmotivated. I didn’t get into high school so I came out to work.” That was very common. It seemed clear that these people were extremely motivated, hardworking, and naturally intelligent, but that the traditional education system was failing them.

The problem is that the traditional education system is: the top two or three people in every class get to go to a good college, while everyone else is basically neglected. There is a huge contrast between the traditional education system, which caters to the elite, college-bound minority and the working class education system, which is very much the opposite.

W4: Was it the financial situation of the migrant workers’ families, who could not afford to pay for education, that prevented the children from completing their studies?

LC: That’s a good question. It was part of the reason. Some workers would explain clearly, “I didn’t pass the test for high school, so I dropped out of school to work instead. Other workers would say, “I obtained a place at a reasonably good school, but my parents didn’t have enough money for me to attend” Or: “They wanted to send my younger sibling, but not me.” Financial considerations were definitely part of the problem, but there was also the question of whether the youngsters had the capacity to obtain a place in school.

I did not get the impression that families invariably short-changed their daughters’ education in favour of their sons’. You definitely hear of that, but in many cases a family would bet on one family member only, irrespective of gender. The parents would give priority to the child they deemed most capable, the child who was doing well in school, regardless of whether it was the son or daughter. All the other family members were expected to work and make sacrifices to help this one person. That was a pretty common model.

W4: What is your view of the status of women in China today? Is the inequality between women and men widening? How do you think men and women can promote women’s empowerment in China today? And, more widely, throughout the world?

LC: The women who are moving to the cities are empowered in certain respects; they can achieve unprecedented financial and emotional independence. However, there’s no consciousness among the female migrant women of inequality, injustice, or a sense of society’s responsibility towards women. This consciousness exists mainly among educated women in Beijing and Shanghai. Female migrant workers are not saying, “Oh my god, society is so unfair to women.” To them, it’s life that is tough.

I think China is still a very traditional society and, as the wealthy grow wealthier, it’s becoming increasingly so in some ways. For example, among the wealthy it’s now considered a status symbol to have a wife who doesn’t need to work. I think all over the world women face certain challenges – they have to find a way to balance career and family. But women in China face special obstacles. For one thing, the political and business worlds are markedly male-centric: in these spheres, so much of business is done while drinking and smoking and socializing in karaoke bars. So it’s very hard for women to break into these worlds, even if they want to. Women who have succeeded in business and politics have done so against great odds, and I admire them for that.

W4: Are you working on any other research/writing projects which you would like to share with Women’s Worldwide Web?

LC: Right now I’m living in the States and writing for magazines. One article I’m working on is about archaeology in Southwestern America, and I guess it ties in with my previous work in that it’s about history and how people view their history. I think it’s an aspect of American history that people don’t really know about – what people were doing here when Columbus came… it’s a little-known story.

My husband and I intend to move to the Middle East next year and learn Arabic. We would like to spend a few years there, writing stories and books, similar to what we did in China, looking for more personal stories. I feel that the Middle East is, like China, a part of the world that is very important but often misunderstood and overly politicized. After living in the Middle East, we’d like to go back to China and see how things have changed.

© Women’s WorldWide Web 2010