“Books open up new worlds for us emotionally, geographically, culturally; by encouraging understanding, they help us to develop more compassionate, rational, tolerant societies, giving rise to a more broad-minded world.”

“Books open up new worlds for us emotionally, geographically, culturally; by encouraging understanding, they help us to develop more compassionate, rational, tolerant societies, giving rise to a more broad-minded world.”

Irene Staunton is co-founder of Weaver Press, based in Harare, Zimbabwe, and editor of Women Writing Zimbabwe, the first anthology of women’s writing in Zimbabwe, illuminating the lives of Zimbabwean women and the difficulties they endure every day as mothers, daughters, wives, and sisters: the linchpins of a society facing HIV/AIDS, desperate poverty, and political crises. Staunton’s work is at once literary, creative, and passionately commited to concretely improving women’s lives by giving them a voice that they would not otherwise have.

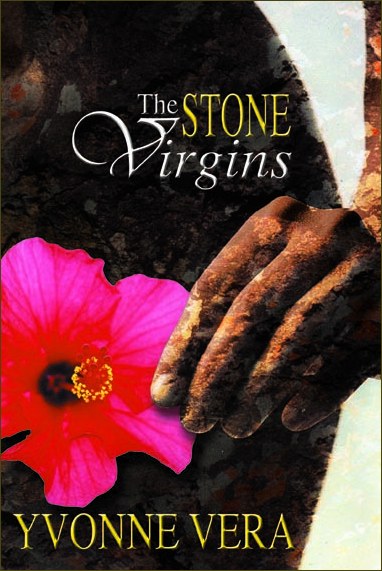

Irene Staunton was born in Zimbabwe and began her career in publishing in the 1970s in London, where she worked with John Calder Publishers. Returning to Zimbabwe after it was granted independence in 1980, she became an editor at the Curriculum Development Unit of the Ministry of Education. In 1987, Staunton co-founded Baobab Books and in 1999 she co-founded Weaver Press. She was also the editor of the Heinemann African Writers Series for several years at the turn of the decade. In 2002, Weaver Press began publishing fiction in addition to non-fiction. Among these books, two notable titles are Yvonne Vera’s The Stone Virgins (2002) and the short story anthology Writing Still (2004), both edited by Staunton.

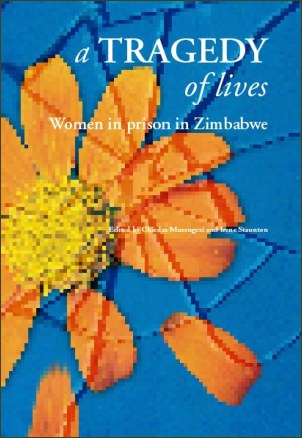

Staunton compiled the first Zimbabwean oral history, Mothers of the Revolution: The War Experiences of Thirty Zimbabwean Women (Baobab Books, Harare, 1989), bringing together narratives of women in the liberation struggle. She also compiled and edited Children in Our Midst: The Voices of Farmworkers’ Children (Save the Children, Harare, 2000). She has conducted numerous interviews and was one of the editors of the Zimbabwe Women Writers titles, Women in Resilience: The Voices of Ex-Combatants (Zimbabwe Women Writers, Harare, 2000) and A Tragedy of Lives: Women in Prison in Zimbabwe (Chiedza Musengezi and Irene Staunton, eds., Zimbabwe Women Writers, Harare, 2000.) Other oral narratives assembled under her aegis include: Our Broken Dreams: Child Migration in Southern Africa (Save the Children, Harare, 2008), and Damage: The Personal Costs of Political Change in Zimbabwe (African Book Collective, Oxford, 2007).

“For me, literature is an incredibly important way of telling the truth,” Staunton says. “In fact, I believe it is more important than history in terms of being able to help us understand the complexities and nuances of any period, any situation.”

1. Please tell us about your decision to return to Zimbabwe after independence and concentrate on publishing and editing Zimbabwean writing? What were your goals in the beginning?

Irene Staunton: Like many people living away from home in the 1970s, I longed for the day when I returned home. It’s the same now for many economic and political exiles from Zimbabwe living all over the world. ‘Home’ is a word with very personal resonance: it embraces the dry tang of dust, the sound of footfalls on baked earth, the heady smell of the first rains, the call of people greeting each other over a distance. It does not necessarily suggest four walls, a house, a job—though, of course, it can.

I didn’t have many goals beyond the goal of returning. But I was fortunate: I quite quickly found work first for the Department of Culture in the Ministry of Education and Culture; and then on to the Curriculum Development Unit, in the same Ministry. Later I was asked to join Hugh Lewin in setting up a small publishing company, under the umbrella of Kingstons, a bookselling chain and parastatal. This new house became Baobab Books and I worked there until 1998, when Murray McCartney and I founded Weaver Press.

A small, general publishing house, with supportive sponsors (and we did have a few, without which we could not have survived) in a developing country and in a new society full of hope: it was a challenging and interesting enterprise. Our role developed around the writers and their very particular, very significant voices.

Weaver Press set out to publish (as did Baobab Books) very good fiction, and to try to ensure that some of the important academic research done in the country is made available to a wide readership.

In a country where purchasing books is not a high priority, general publishing is a fairly precarious endeavour. But its role is significant: I believe that good fiction is a valuable way of recording experience in all its diversity and shades of ambivalence; and I believe that every society should have access to, and be able to discuss and debate, academic theory and analysis – this is how people remain informed, dynamic and able to robustly challenge the sweeping generalisations made by nationalist propagandists.

2. You’ve published many books on women’s experiences. What brought you to work on this particular topic? What do you think are the most important reasons for focusing on women’s voices in Zimbabwe, whether they are established writers of fiction or rural women who lack the resources to make themselves heard?

Irene Staunton: I was very fortunate in that my parents taught us to respect people from all walks of life and showed us that what mattered was not money or status but warmth, compassion, humour and integrity – values rooted in self-respect and human dignity. My mother was also involved in the Federation of African Women’s Clubs, doing voluntary work that she enjoyed very much and which gave me, through her, access to strong, gentle, humorous women working long hours for their families in rural areas.

Irene Staunton: I was very fortunate in that my parents taught us to respect people from all walks of life and showed us that what mattered was not money or status but warmth, compassion, humour and integrity – values rooted in self-respect and human dignity. My mother was also involved in the Federation of African Women’s Clubs, doing voluntary work that she enjoyed very much and which gave me, through her, access to strong, gentle, humorous women working long hours for their families in rural areas.

In my experience, rural women – who tend to be disadvantaged economically and in terms of education – are emotionally very honest. They are not looking over their shoulders at their audience; they are saying what they think and saying it forthrightly. You do not need education to be wise; you need insight and reflection, which these women have in abundance. In addition, rural women are often very generous with their time, they treat one in a matter-of-fact manner, as an equal, and they are always supportive of projects that enable their voices to be heard. These qualities make our oral history projects such a pleasure.

Because of my childhood experience with rural women, I began asking myself, after independence: who is collecting the voices, the stories, of rural women? — women who had been pillars of strength for their families and communities during the war. This question gave rise to Mothers of the Revolution, my first collection of oral testimony.

I have worked with fewer female fiction writers than male, and we receive many fewer manuscripts from them (for reasons mentioned below). When it comes to working with an author to develop a text, the gender of the writer matters very little – we are all working for the book, for the story. Writers are necessarily very sensitive to the world around them, and they seek to reflect its variety through their unique interpretation.

3. What are the barriers to women’s expression in Zimbabwe? How do family pressures or self-censorship affect the state of women’s writing or writing about women? How does it compare with state censorship? And how do you, as a publisher, and they, as writers, overcome these challenges?

Irene Staunton: Well, it has been said often enough that women who want to write are less able to find the time or the peace to do so because the burden of domestic responsibilities falls more heavily on them than it does on their male counterparts. Moreover, women tend to be more self-critical of their own work than do men. Ninety-five per cent of the unsolicited manuscripts we receive at Weaver Press (and it was just the same at Baobab Books) come from young men under the age of 25. Quite often they are accompanied by a note that reads, ‘I am sending you my manuscript for publication,’ i.e., there is no question in the minds of these young aspiring writers that publication will follow submission as naturally as night follows day. Women seem to be more aware that their work will have relative merit – perhaps they read more widely – and to appreciate that there is a process of selection and assessment. Women tend not to situate publishers at the end of a demand, nor to assume that the desire to write makes one a writer any more than the desire to be a doctor entitles one to a medical degree.

To date, I think one can safely say that there is no censorship of fiction in Zimbabwe, possibly because so very few people buy books that the state has little to fear from them. Certainly censorship does not seem to affect how people write, whether they are published or unpublished. A good writer has a sense of integrity that is hard to compromise. That being said, fear is a palpable force. One may try to counter it with Churchillian sternness by telling oneself that ‘there is nothing to fear but fear itself’; I suspect this provides little real comfort; fear is unfortunately a contagious force.

4. Your work helps people to tell their stories, bringing these stories to a wider audience. Would you ever consider writing in your own voice?

Irene Staunton: Frankly, I am not good enough.

There are so many skills needed to be a very good writer. Besides the ability to tell a story and to imagine yourself into the hearts and minds of very different characters, you need a very good ear, a good eye, a great skill with words, as well as a penetrating intellect that allows you to see the deeper connections, the philosophical underpinning behind all good writing.

5. Among the different books you’ve researched, which was the most difficult? Which had the biggest impact on you?

Irene Staunton: This is a difficult question because every book has an impact and has mattered to me in a different way, but perhaps the two that gave me the greatest pleasure were Mothers of the Revolution and Children in our Midst. The first because, together with my translators – Margaret Zingani and Elizabeth Ndebele, in Mashonaland and Matabeleland, respectively – I went out to the women’s homes, where the three of us were always given a warm welcome. And then the women had such stories to tell, stories that were crying to be heard – and indeed we did sometimes all find ourselves in tears, when we heard them. One often felt that telling the story was a form of unburdening, of release, and it was humbling to find oneself the vehicle of these many life histories.

Children in our Midst was also a lovely experience because, with Save the Children, I went out to farm schools in Mashonaland, where I would talk to a particular class and ask the pupils questions about their lives and then invite them to write down what they had experienced and what they thought about this or that issue. I was working with children from about eight to fifteen years of age, and they took us seriously when we explained that although their stories might not directly help them, they might help SCF to help other farmworkers’ children in the future. Children have a lot to say when you stop to ask them; and I believe that having them write rather than speak provided them with a degree of freedom that they night not otherwise have felt – writing is a private activity, speaking a public one.

Since the farm invasions, I often wonder what has happened to all these very young people who longed for a better future and told us: ‘A child needs to be cared for like an eagle’s egg’ (Mwada Ruwa aged 13); ‘Education is my tomorrow’s sunshine’ (Pangani Mucheki, aged 13).

We live in an age in which we believe testimony is of value per se, and this is a point of view to which I can subscribe. When one has suffered, knowing that one’s suffering has been heard is a step toward personal healing. It is also a step toward the conviction that your difficult experience was not pointless or wasted, but can be heard, read, seen, and may prevent someone else from suffering similarly in the future. The story of your experience may help to prevent governments from making decisions and behaving in ways that render their citizens victims rather than equal participants in the development of a state, a culture, a way of life …

You told the Edinburgh Review that “fiction is more important than history”; it can tell certain truths more effectively than history can. As a writer of non-fiction, and a publisher of both fiction and non-fiction, do you see Weaver Press as an engine for social change? As an instrument to improve people’s lives?

You told the Edinburgh Review that “fiction is more important than history”; it can tell certain truths more effectively than history can. As a writer of non-fiction, and a publisher of both fiction and non-fiction, do you see Weaver Press as an engine for social change? As an instrument to improve people’s lives?

Irene Staunton: Goodness! What large questions. I think the answer to both is: probably not. Rather, I hope that each book, whether fiction or non-fiction, is a very small brick in the constantly evolving structure of knowledge. Publishing a book, like writing a book, provides another way of thinking, seeing, feeling and reflecting; but books must then be read, absorbed, thought about and discussed, and one has little influence over this process.

Moreover, in Zimbabwe, and perhaps in many other countries and societies, one frequently hears what has now become a (complacent) platitude: ‘We are not a reading culture’. In some ways, this is true. Most schools do not have libraries; there are no free-reading periods except possibly in the private schools. So the attitude to books developed in schools is often reductionist: books are simply regarded as tools for passing exams. Poor children have no option but to think otherwise. Middle class children are surrounded by the competition. One teacher at a private school recently told me that, when he gives his students a new book, the response is often, ‘Oh, Sir, you don’t expect us to read all that, do you?’ Accustomed as they have become to two lines of twitter, reading 80 pages, even of the most wonderful novel, seems like a mammoth task.

It has always seemed to me that books open up new worlds for us emotionally, geographically, culturally; by encouraging understanding, they help us to develop more compassionate, rational, tolerant societies, giving rise to a more broad-minded world. But perhaps these aspirations will now be fulfilled through the internet when you only have to read a few lines to engage with a thousand ‘friends’? And are they ‘friends’ because they mirror your existing beliefs, or because they help you to see the world?

I guess the jury is still out on this one.

6. What dimension(s) of your work at Weaver Press do you consider most important?

Irene Staunton: Weaver Press is very small. There are only three of us, and in many ways we work more like a small NGO than a company. ‘Important’ is an adjective that makes a claim, and I’m not sure that I would want to do that. However, I believe that it is the good editors in any publishing house who play the most significant role, and working with an author on his or her book to try to make it finer, sharper, clearer and deeper is in many ways an intimate experience, one you only share with the author in discussion and reflection, weighing each word for its significance, each sentence for its rhythm, each idea for its tone.

A good writer is always ruthlessly honest; evasion leads to sentimentality, weak characterisation to thin plot, poor writing to circumlocution, pomposity or shallowness. There are many features that make a good book one that people want to read and one which allows them to grow. Editors are a bit like stage-hands: the play can’t go on without them, and yet their role is necessarily in the shadows. It is, however, interesting to see how many writers acknowledge their editors – the third eye is of value.

© Women’s WorldWide Web 2011