Warning: This article includes graphic content some readers may find disturbing

W4 talks with photojournalist Walter Astrada, 3-time recipient of the renowned World Press Photo prize, about his project to highlight the global imperative to end violence against women.

Copyright: Walter Astrada

“I want my pictures to educate people. We can use photos like mine to make clear: There is something wrong with our culture of violence, and it has to change.”

Award-winning photojournalist Walter Astrada has for years used his lens to shed light on the stark reality of violence against women in countries across the globe. W4 was honored to meet with Walter to discuss his project, which culminates in a chapter documenting domestic violence in Norway. “I really wanted to finish this project in Norway,” Astrada says, “because it shows that violence against women happens everywhere. Norway is one of the richest countries in the world, but, even there, violence occurs. We have to get people to understand the extent of the problem.”

Born in Buenos Aires in 1974, Walter Astrada spent most of his early life surrounded by resilient women. “My mother was a single mother, and I didn’t have a father figure until I was thirteen, when my mother married and I moved to live with her and her husband. Before that, my mother was working in another city to make money to raise me while I was living with a friend of hers who was divorced with four daughters. Basically, I was living in a family of women.”

“Some people say, ‘Your pictures are too raw, too direct,’ and I respond by explaining that I can’t be taking artistic pictures of this issue, because it’s a woman, a human being, who is suffering. I really need to show what happened to this person. I can’t do artsy pictures. I have to show the situation, the person, how they are, and that’s it.”

Walter’s mother was 18 years old when she gave birth to him and was forced to leave school and begin working in order to be able to pay for food and care for him. Astrada explains: “In Latin America, when a girl gets pregnant at school, she’s sometimes expelled. But the schools aren’t expelling the boys who impregnate these girls. […] The most important tool that society can provide, education, is being taken away from these girls just because they got pregnant. And, at the same time, you don’t talk to them about sex in schools, you don’t explain to them how they can protect themselves and you don’t allow them to have an abortion if they need one. It’s crazy.”

Walter’s awareness of the inequalities suffered by girls and women grew even deeper after he launched his photojournalism project on violence against women in 2006. That year, while living in Spain, he stumbled upon an article about Medecins Sans Frontieres’ work in Liberia to repair fistula, a severe gynaecological condition that results from sexual violence. At the same time, his local research revealed to him the tragic preponderance of domestic violence-related deaths among women right there in Spain. On a global level, his eyes were further opened as he gathered information on rape in Congo, rape during the Rwandan genocide and the war in the Balkans, the kidnapping of women in Juárez, Mexico, femicide in Guatemala, acid attacks and self-immolation in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, and the foeticide of girls in India because of the preference for sons over daughters (not least for dowry reasons).

In the face of this global pandemic, Walter prepared a grant proposal for a project documenting violence against women. “I wrote a proposal to do a project on violence against women in different countries and on different continents in a way that would enable me to present this problem as a worldwide problem. I chose one country on each continent and sent in my application. I wasn’t lucky enough to win the grant, but I came in second. At that point, I was like, “OK, I didn’t win, but somebody saw something in this proposal – maybe it’d be good to launch the project on my own.”

Self-financed, Walter bought his plane tickets and set out to begin the “Femicide in Guatemala” chapter of his global series on violence against women. One of the many powerful photos from this chapter (right) was awarded 1st prize by World Press Photo in its Contemporary Issues category in 2006.

Copyright: Walter Astrada

“In Guatemala, over the last 12 years, more than 5,000 women have been killed. Only perhaps 30 cases have resulted in prison time for the perpetrators, which is an incredibly small number. There’s another problem, too, which I’ve seen for myself: if a murdered woman is wearing a skirt or sandals, has her nails painted, isn’t wearing underwear, or has a condom in her wallet, automatically the police say that she’s a prostitute and they don’t carry out a proper investigation of her murder. If you are married in Guatemala and you want to get away from your wife, it’s very easy – just kill her or send someone to kill her and dress her in a way to make the police think she’s a prostitute.”

Walter’s photos depict a brutal, tragic reality – a reality that some do not want to confront: “Some people say, ‘Your pictures are too raw, too direct,’ and I respond by explaining that I can’t be taking artistic pictures of this issue, because it’s a woman, a human being, who is suffering. I really need to show what happened to this person. I can’t do artsy pictures. I have to show the situation, the person, how they are, and that’s it.”

“[Women’s solidarity groups] really know what is going on, they really know the people, and they really know the needs of the people. Even if they don’t always have so much money, in general they’re doing great things. They’re meeting together and trying to do their best.”

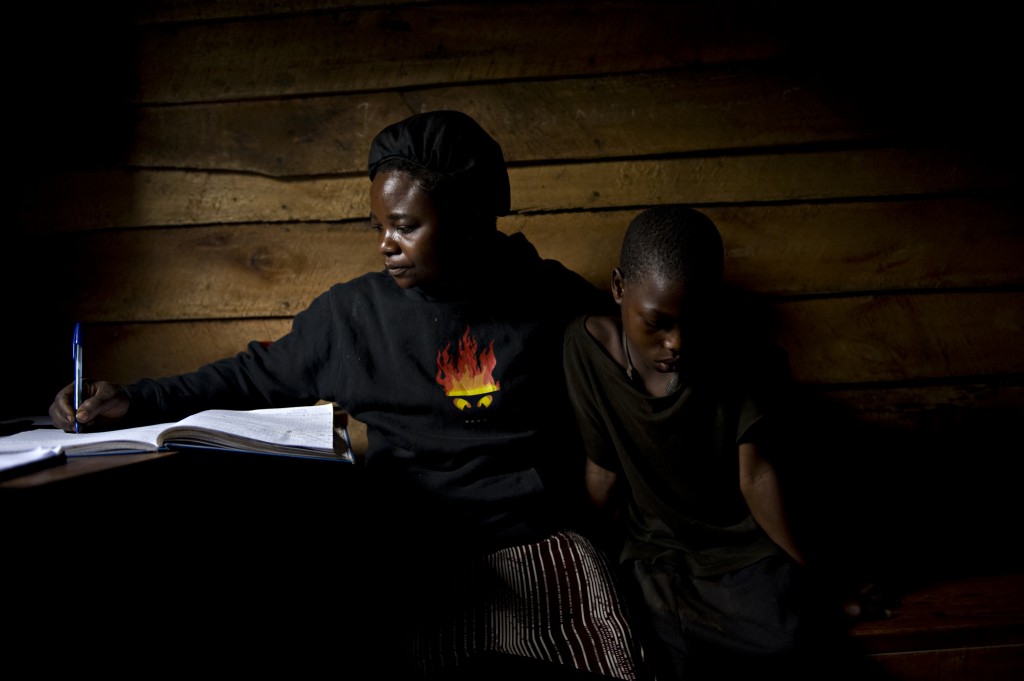

After Guatemala, Walter went on to meet women who have experienced brutality and violence in Eastern Congo and India. He hoped that, upon seeing and hearing their stories, the world would come to recognize our shared prerogative to act urgently to put an end to violence against women. Walter shares the shocking and profoundly moving story of one woman, Mama Masika, in Congo:

“After the genocide in Rwanda, in 1994, a lot of Hutus crossed the border into eastern Congo. After that, the Rwandans decided to follow after them and that’s where the war in Congo began. The husband of Mama Masika was killed by Tutsi soldiers. They killed him and cut him into pieces. They forced Mama Masika to reassemble his body parts and make a bed with it . Then 12 soldiers raped her on top of her husband’s reassembled body. At the same time, her two daughters were also raped. Of course, she had a complete breakdown as a result of the trauma and was taken away to the hospital.

After six months in the hospital, she returned to her home and saw her two daughters, who were now pregnant. She didn’t understand how her daughters got pregnant. Somebody had to explain to her what had happened, which made her faint, and she was again taken to the hospital. This time, she was accompanied by another woman who offered her psychological help.

Copyright: Walter Astrada

After her recovery, Mama Masika resolved to open a center to help other women survivors of rape. You can see her, in my photo, writing in a book. Every day she writes down the testimonies of all the women who have been raped and who come to her center for the morning-after pill, anti-HIV prophylaxes, and support. For me, this woman is just amazing.”

Throughout the duration of his project, Walter relied heavily on the help of local groups of women, like the one founded by Mama Masika, who have joined together in solidarity to support survivors. Walter explains how these groups are often more effective than larger organizations and governments: “[Women’s solidarity groups] really know what is going on, they really know the people, and they really know the needs of the people. Even if they don’t always have so much money, in general they’re doing great things. They’re meeting together and trying to do their best.”

In Walter’s opinion, education remains key to putting a stop to a culture that condones violence against women: education to empower girls and women, and education to raise global awareness of the issue. “Some have seen my project as a testimony – a testimony for hope that in the future this violence will no longer happen. Sadly, I don’t see it ending any time soon, but when it does, we will have documented that it happened in the past, documented that we were actually that brutal.

Often when people are just talking about an issue, others don’t care. But if you show them photos of the issue you’re discussing, it can be more powerful. People then say, “Oh, wow, this is real.” »

Tragically, this IS real, but you can help to put an end to violence against women. Leave a comment below, share this article across your network, and visit our projects portfolio to see how you can help our field partners to support survivors of violence and empower girls and women through education and training.

To learn more about Walter Astrada and his work, we invite you to visit his website.

© 2017 Women’s WorldWide Web (W4)